|

Half the fun of reading experimental fiction is figuring out what the author means. The other half is admiring the way she does it. Dart tackles the issue of words themselves—the “language-game” whereby reality is shaped by the words we use. Words seek to bridge the unbridgeable gap between what can be expressed in language and what can only be expressed in nonverbal ways. To help the reader understand, Dart sprinkles Wittgenstein's quotes throughout, using his philosophy as a protective bumper, a soft shield between her experience of a childhood tragedy and her memories of it. Like words, memory can be a tricky tool, and sometimes philosophy, psychoanalysis, and remembrances from other family members are needed to make sense of events and remove doubts.

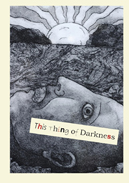

“Doubt, according to Wittgenstein, only comes after belief.” The protagonist named “L” believes that when she was four years old, with the limited vocabulary and perspective of a child, she saw her father try to kill himself. But as an adult with a now vast vocabulary, she begins to doubt what she saw and wonders if the incomplete language of childhood plays a role. After all, she learned to read, like so many in England, with the Peter and Jane Ladybird books, which taught a limited technique using key words called “look and say” from a warm middle-class perspective quite foreign to her. What ensues is a surreal and beautiful journey through “this thing of darkness” (a quote from Shakespeare’s The Tempest), led by concepts and objects Dart knows (she thinks) to be true. In oversized pages with an abundance of white space, floating text, highlighted sections, photos, drawings, and verbal jousting, repetition of these particular words burns true.

Generally, experimental fiction uses word repetition to create a unique voice and further the narrative. Repetition underscores key points, creates a rhythm, strengthens emotional impact, and emphasizes deeper meanings. William Faulkner’s experimental novels use word repetition as a literary device, especially in The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom! In the former, the word “time” is used repeatedly to show the protagonist’s obsession with the past and inability to escape it. In the latter, narrative repetition represents the character’s search to understand the present by facing the past. Virginia Woolf also plays with language, using stream-of-consciousness narratives and taking liberties with timelines. James Joyce and Samuel Beckett are likewise in this club, and more modern members include David Foster Wallace, who invented words (as did J.R.R. Tolkien) and used a unique cadence.

Experimental fiction also frequently uses unconventional structures, such as photos, drawings, ticket stubs, and recipes. For example, Herman Hesse illustrated his own fairy tale, “Piktor’s Metamorphoses.” K.B. Carle used crossword puzzles in “Vagabond Mannequin.” Oreo, by Fran Ross, employs restaurant menus, advertisements, and diagrams. Their very personal approaches, much like Dart’s, stimulate the imagination and defy convention.

While she has a PhD in creative writing from the University of Sussex, Dart overturns literary conventions: the classic beginning, middle, and end; clear goals of the main character; normal formatting; and action that moves the story forward. But the story does progress, and the main character’s goals are met in a unique fashion. By squinting with the third eye and reading like an art or music lover, it’s apparent from start to finish that Dart's use of particular symbols matter: a hand, a dark door with a hand-shaped knocker, the war between doubt (warm) and certainty (cold), the plant named Viburnum tinus, the color red, the definitions of the noun “proposition,” butterflies, dreams, and fetuses. Dart carries these disparate symbols—depicted in words and pictures—throughout and magically connects them.

Dart’s philosophical musings and mixed media on thoughts, language, and memories seek to lay bare one specific memory: at the age of four, did she or did she not see her father attempt suicide with a sword? This leads to further questions. Are memories true and certain? How much does language get in the way of truth? When do linguistic missteps begin, and with what consequences? Dart’s unique offering is both entertaining and potentially life-changing.

RECOMMENDED by the US Review

Next Focus Review

Previous Focus Review