|

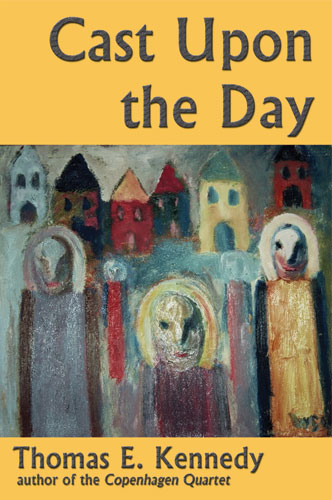

Cast Upon the Day by Thomas E. Kennedy Hopewell Publications

book review by Liam MacSheoinin

"Nine A.M. sharp and Flood sits sober-faced, listening to quiet voices speak important things."

Cast Upon the Day the new story collection by the award-winning author of the Copenhagen Quartet, Thomas E. Kennedy, is a dactylonomer’s delight: eleven brilliantly crafted, unforgettable fictions. The erudite, insightful introduction provided by Robert Gover, author of the acclaimed One Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding, makes a point of declaring Kennedy’s contribution to present-day literature. Remembering Milan Kundera’s descriptive phrase re the self-absorbed protagonist of Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, Gover declares: “That phrase ‘the soft gleam of the comical’ is what distinguishes the short stories in Kennedy’s most recent collection, Cast Upon the Day.”

Gover further declares that Kennedy and Cast Upon the Day “does for our time something akin to what Flaubert did for his.” High praise from a writer Gore Vidal calls “a literary Halley’s Comet.”

In what I think is the best story of a collection of eleven palpable hits, “South American Getaway” (after the theme music of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid), Charles Feuk, the protagonist, awakes one morning with the sound of music in his ear. Not, as it seems, the clock radio, his usual reveille, but instead Feuk’s mind has become a transmitter of sorts, as “Swingle Singing” (“South American Getaway” getting the Ward Swingle treatment) haunts his waking life. Up until that day, Feuk had been living the proverbial charmed life: darling of his employer, well-dressed, debonair, irresistible to women. Soon, the appositely named Feuk watches, “soft gleam of the comical” ever-present, as his once near-perfect life devolves into a living cauchemar.

“A Cheerful Death,” another gleaming example of Kennedy’s genius for the tragicomical, centers on the flight of a businessman from the IRS. The self-destruction of its main character, Jastovich, is reminiscent of Kennedy’s classic tale of excess, “The Great Master.” The unnamed narrator in “The Great Master,” unhappy with “just another grey quotidian,” decides to eat everything in the house. The Great Master is good to his word and consumes every square centimeter of food in the house until, literally, it no longer can support him. As the John Mellencamp song puts it: “It all comes tumbling down!” These two stories depict characters unwilling to commit to normative societal attitudes. These are men whose “fatal flaw” is their unwillingness to share. The Great Master won’t even share his name with the readers. Jazz, one of the many incantations of the protagonist of “A Cheerful Death,” also comes to a bad end (as its title suggests).

The Irish Catholicism of Kennedy’s youth is present in his entire oeuvre. His Pushcart Prize–winning story “Murphy’s Angel” has remained with me from the time I read it in the late nineties. We learn early in the story that the eponymous protagonist, Murphy, has a languishing angel in the basement of his suburban home. To Murphy’s chagrin, there’s nothing he can do to alter the condition of his angel. Especially, with his wife grousing about the angel’s presence in their home. Tellingly, later that evening, Murphy’s troubled son, a total suburban brat, refuses to watch Going My Way with his father. Murphy’s son hates Bing Crosby (Father O’Malley). Murphy, however, also admits to himself to not liking Crosby very much. Disappointed, Murphy retreats to the basement; the angel expires, signaling the death of Murphy’s Irish Catholicism.

In “Communion,” the most Irish Catholic story in this current collection, French, an Irish Catholic professor living out West, returns to Queens to attend the funeral of his matriarchal grandmother. The power and virtuosity in which Kennedy describes the important passage is typical of this poet in prose. The contrast between French’s steak dinner the night before the Communion portion of his grandmother’s Requiem Mass highlights Kennedy’s uncanny narrative powers. French’s brief fantasy of bedding the waitress serving him is an exquisite economy of description: “She had a warm smile, such a pretty mouth. ‘Perfection,’ he said, and she looked glad. He glanced at her finger for a ring, there was only a little birthstone, which reminded him again of his loneliness.”