|

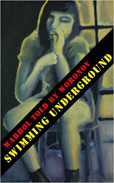

Swimming Underground: My time at Andy Warhol's Factory

by Mary Woronov

Montaldo Publishing

Actress and artist Mary Woronov paints Warhol-like cinema of her time in the Silver Factory and Andy Warhol’s inner circle during the late 1960s. Woronov was most famously depicted during that time as Hanoi Hannah in the film Chelsea Girls—one of many Warhol “films” and “screen tests” that were never meant to be viewed in the classic linear style of storytelling, but rather the endlessly interpretive impression of art. In fact, Woronov would eventually come to see them as video paintings, often displayed as background pieces while the Velvet Underground played and the party rolled.

The story begins as she abandons college art studies to join the scene at the Silver Factory—a Manhattan converted warehouse space covered with silver foil and the spiritual blood of its inhabitants. There, she crossed paths with famous characters such as Lou Read, Billy Name, and the Duchess. The Factory's inhabitants have been glorified, if not entirely airbrushed, by history, but Woronov crafts more personal images and more realistic stories than those of legend. Honesty is the working model here and particularly in the depictions of herself. She thrashes back and forth between her childhood, as well as a dual Manhattan existence of near normality and the anything goes lifestyle of the Factory. The roiling, angry person beneath Woronov’s speed freak skin is not always a pretty picture, but don’t peel the layers off anyone if you can't stomach the monsters that lurk inside.

Her memoir reveals a candid portrait of a young woman struggling for independence, meaning, and, eventually under the forceful hands of drug addiction, her own survival. This soil is tilled by many artists attempting true expression or perhaps any person trying to be born into their own reality. Woronov, at least at first, built an inner wall against influence and even love, but the all-consuming world of the Factory was not her own and therefore impossible to control. It was Andy’s world, filled with excess, art, and the socio-non-normal of the time. He lorded over it with a disarming and demure exterior that was expansive on the inside and one step ahead of the scene he created. Brilliant, calculated, and devious, he left doors open for willing souls and captured moments that suited his sensibilities. Woronov admits that she was often trying to please an unstated set of Warhol directions, but she and the others didn't go anywhere that they weren’t willing to go on their own.

The writing has moments of beauty and insight. The most memorable sentences arrive when her anger explodes inside and leaks out as sarcasm and even sheer violence. She names each of these moods and personalities as alter-egos and alter-animals. It’s a thrilling, disturbing ride that becomes comfortable and ultimately tragic, and we all like to see the crash, don’t we? Half of the traffic jams on the freeway would be eliminated if this weren’t true. We all want to glimpse our own mortality through others and especially from someone who teased it forward in their youth.

Like an art museum discussion, the articles in the appendix add poignancy to the book's narrative. In the end, Swimming Underground is not a tragic tale. Woronov falls in love. Damn it. But it’s a love that can never be. Hello, life. She eventually leaves Warhol and pursues a career in film and art. This memoir is a story of first escaping the American Dream—the version we are force-fed as children—and then employing what freedom is left in America to her advantage in order to gain herself. It’s a compelling risk that only those who have done it know about. Woronov can tell you.

RECOMMENDED by the US Review

Next Focus Review

Previous Focus Review