|

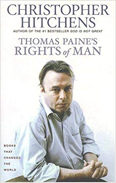

Thomas Paine's Rights of Man

by Christopher Hitchens

Grove Press New York

Now that radical elements are attempting to erase history, Thomas Paine might laugh in his grave. As the singular most important figure in the birth of modern democracy, the promoter of human liberty, and the author of an American bestseller only eclipsed by the Bible, Paine should have a monument in Washington, DC at least as big as the “founding fathers,” but he has been mostly forgotten—and that occurred before he even left the planet.

Born the son and later apprentice of a corset maker, Paine stumbled into London after escaping death at sea during the outside of The Seven Years War between England and France. There his Quaker roots crossed paths with the freethinking denizens of the city. He fumbled through professions and a marriage, while expanding in radical thought. In 1774, he appeared in Philadelphia alone with a modest letter of recommendation and a recent acquaintance with Benjamin Franklin. Two years later, he published a half million copies of Common Sense—a pamphlet that challenged British authority and monarchy in plain and ingenious language. Often referred to as the greatest American bestseller, Common Sense was either read by or to read to nearly every colonists and became the catalyst that altered history.

Later, with The Rights of Man and The Age of Reason, Paine influenced generations forward and still does today. This latter work, which challenged the papacy, rejected the fantastical elements of belief in God, and even criticized George Washington, caused a backlash among his peers and isolated him from society. After a stint abroad fanning the flames of The French Revolution, the father of two national freedom movements spent time in prison, narrowly escaped execution, and returned to America in anonymity to die nearly a pauper in the New York. Like a true zealot, Paine had alienated himself from even his staunchest supporters in the end.

With his usual wit, economy of words, and deft deployment of facts, Hitchens paints a wonderful and honest portrait of Paine centering around The Rights of Man—a brilliant discourse on the nature of humanity and that rights are inherent to man and not bestowed by any earthly authority. It is existential and timeless as it is practical and current. Hitchens never minces words or arguments, and it’s clear that he is passionate about his subject matter. If Paine was a singular gift to humanity, then Hitchens’ handling is reverent and as needed now as much as ever.

RECOMMENDED

Next Focus Review

Previous Focus Review