|

Children instinctively seek provision and protection from their parents. A love bond develops early and is generally reciprocated. A fierce loyalty emerges, one that sometimes causes children and parents to make tremendous sacrifices for each other. But what happens when something interferes with that love bond, an intruder that shorts it out either periodically or permanently? Stack's heart-wrenching memoir tells the painful story of how during a life-changing road trip his father's alcoholism succeeded in fraying most of the final cords that were keeping him attached to his children.

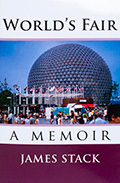

The Stack family had been disintegrating for several years before 15-year-old James' mother told him to pack for a trip to Canada and the World's Fair with his father, 18-year-old twin brothers Peter and David, and 19-year-old sister Geraldine (Gee). Legally separated in 1960, the Stacks divorced in 1964 after "four messy years of shouting and Momma's furs flying." While she and the oldest Stack child, Bonnie Ann, who was married, wouldn't be making the trip, James' mother saw it as his father's last chance with his children. So in the muggy summer of 1967, Daddy loaded James and his siblings into the white camper he had purchased for the journey and headed north from South Carolina to Montreal.

Trouble began almost immediately after Daddy learned that his kids had found and thrown out all of the liquor he had cached in the camper while he was driving. For their part, the Stack children were determined to try and keep their father sober on the trip so that they could all enjoy Expo '67 together. And there were a few enjoyable moments during the first days after they arrived, but Daddy always managed through trickery or plain stubbornness to find the alcohol he craved in the restaurants and bars attached to the various pavilions they visited. Once he was arrested for public drunkenness and the children had to return to their campsite alone while their father slept it off in a jail cell. The next time he was arrested the police brought him back to the campsite and turned him over to his family for the night. But this proved to be a crucial mistake, because Daddy turned violent, pulled a gun from one of the drawers while struggling with the twins, and then threatened to kill them. After managing to secure the fallen pistol, Gee had to force her father at gunpoint to leave the camper. Gee and her brothers then drove off and headed back to South Carolina, leaving Daddy alone to find his own way back to the United States.

Stack expertly recreates the atmosphere of the mid-sixties by recalling both the excitement that the Expo generated and the prevailing attitudes that many had toward those who were different, whether foreign, from another region of the country, or from a broken home. But the author's skill with the book's backdrop takes a distant backseat to his poignant portrayal of a family in crisis. Stack's writing is raw and earthy, frequently salted with the strong and abusive language he heard growing up. He captures superbly the love and longing the Stack children had for their father coupled with their mounting distaste and growing hatred, a tension that often resulted in violence and abuse toward each other. The author is also not afraid to lay bare for his readers his sexual confusion during the time period, nor to hide his youthful obsession with sexual self-gratification. There is a stark honesty in this work, a refusal to sugarcoat the events or the personal shortcomings of each of the characters. Stack's memoir has the expert flow of the finest fiction melded with the pathos of a true and heartbreaking family narrative.